Lettie Helps with the Challenge

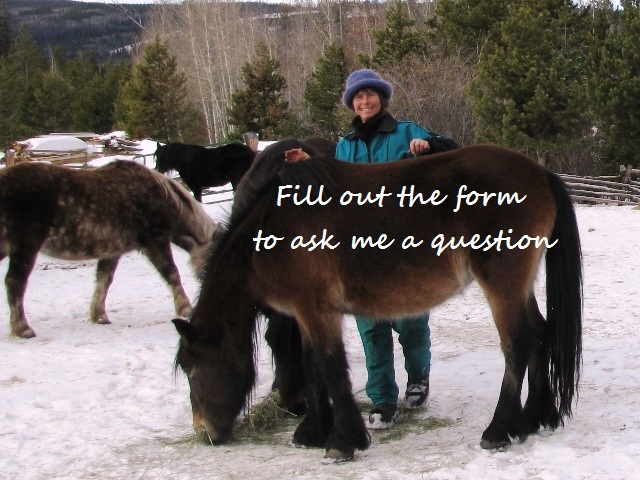

/With the cooler temperatures of fall, I began to ponder the Fell Pony Society 96 Mile Queen Elizabeth II Memorial Challenge that I signed up for in the spring. At the start of summer, I had only completed 13 miles, and then I took the hot days of summer off. The challenge has to be done by the end of October, so I know it will be a push to finish it.

Lettie up high on the hill, rudely interupted from grazing to have her picture taken!

Fortunately, the ponies that I signed up to assist me with the Challenge, including Willowtrail Lettie and Willowtrail Aimee, seemed, like me, more interested with the cooler weather. In all, I signed up three youngstock, including Lettie and Aimee, and one mature pony. Aimee and Lettie spend most nights out on the hill with two mares. They sometimes are up quite high, as shown in the picture here. My thinking regarding including the youngstock in the Challenge was that hand walking them often and in new environments is good experience for them and solidifies their leading skills. And walking with me is quite different than how they spend most of the hours of their days, so it’s good for them to live a domesticated life for a few hours!

One walk with Lettie contained many of the new experiences that I hope for on our outings. We walked along the ranch lane a half mile out and back, so a mile total. While walking, we met a pickup on the lane and then a tractor. We passed cows with calves in pastures along the lane and wild turkeys wandering around. Lettie was fine with all these features of our walk. So I was surprised what caused her to go on high alert.

Lettie suddenly on high alert on a walk for the Challenge.

We got almost to the end of our half mile outbound walk when she stopped and raised her head as high as it would go. I followed the direction of her gaze and smiled. She had spotted a mature bull in a pasture. The bull was moving in our direction, though nearly 100 yards away and over a fence. Then I watched Lettie shift her gaze slightly, and there was another bull also moving in our direction from similarly far away. I think the bulls were headed to a favorite midday resting place, so their movement had nothing to do with us. Nonetheless, these animals are impressively massive, and while Lettie sees cows and calves quite often, she hasn’t had the chance to see mature bulls very often, especially away from her herd and all together.

We’re having fun together working on the Challenge!

Eventually Lettie relaxed, and we completed our walk without incident. I was pleased that she didn’t get busy feet when she saw all these new sights. Much safer for any humans she is with. Aimee has been similar when we’ve been out and about, so we’ve had a lot of fun together all through September.

© Jenifer Morrissey, 2023

There are more stories like this one in my book What an Honor, available internationally by clicking here or on the book cover.